3.6 Firms' Short-Run Decisions to Produce and Long-Run Decisions to Enter or Exit a Market

5 min read•june 18, 2024

Jeanne Stansak

dylan_black_2025

Jeanne Stansak

dylan_black_2025

Entering and Exiting a Market

A perfectly-competitive market is a market marked by a few key points. This section will focus on the fact that a perfectly-competitive market has many sellers and low barriers to entry. This means that, in theory, anyone can open their own business in a perfectly-competitive market, and anyone can leave the market at will. This section will help us understand how and why a firm may enter or exit a market, but first, let's get some definitions in place.

A firm enters a market when it opens business and begins selling product. That is, when their quantity isn't 0. A firm exiting the market is not the same as completely going out of business. Instead, a firm exiting a market means the firm has decided not to produce any quantity. The actual firm may still "exist," but for our purposes exiting a market means you don't produce anything.

The Shut-Down Rule

In the short-run, firms will decide to operate or shut down by comparing total revenue to total variable cost, or price to average variable cost (AVC). This is because in the short run, there will always be a fixed cost regardless of quantity, even if quantity is zero. They will shut down when the price of the good or service drops below the average variable cost. We call this the shutdown rule, which states that the firm should continue to operate as long as the price is equal to or above the AVC.

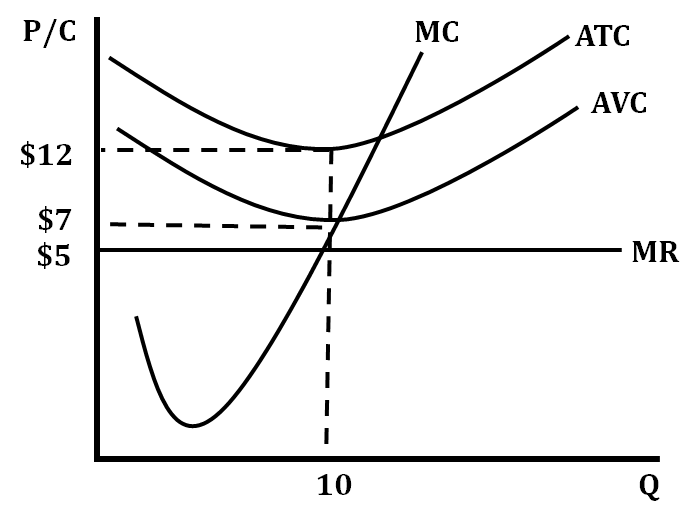

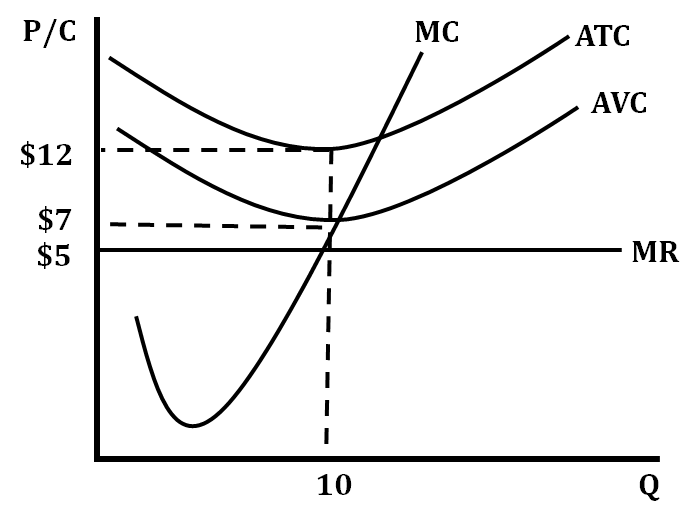

In the graph above, you can see that at the profit maximizing (MR = MC) quantity of 10, the price is below the AVC of $7. Based on the shutdown rule, this particular firm would choose not to operate and, instead, pay their fixed costs because that would be less than its overall costs if it were to continue to operate.

This can be summed up in the following:

If you cannot cover your costs for producing goods, then you shouldn't produce any goods at all. Instead, take the hit on your fixed costs only.

Let's look at this using specific numbers. The total revenue this firm makes when it produces at the profit maximizing point is 5 x 10). The total costs are 12 x 10). If it chooses to operate they would incur an economic loss of 50 - 70). However, if they choose to shut down, they would only be responsible for their fixed costs, which in this case would be 50.

Remember the vertical difference between the ATC and AVC represents the AFC and that is how we determine that the AFC is 12-50, which is less than their economic loss if they chose to continue to operate.

Fun fact! This is out of scope for AP Micro, but producer surplus for a firm is actually exactly equal to their variable profit. That is, PS = TR - VC (not TC). When price is less than variable cost in a perfectly competitive market, the firm will have negative producer surplus - that is, they lose surplus! This is part of why the shut-down rule exists.

Long-Run Decisions to Enter or Exit the Market

When a firm is earning either a profit or a loss in the short run, it serves as a guide for other firms to either enter or exit the market. If the firm is earning a loss while still continuing to operate, then we will see firms exit that particular industry in the long-run. Remember, in the long-run, all inputs are variable, meaning a firm can completely avoid their costs by exiting the market (since no costs are fixed in the long-run!). Thus, if firms are making a loss at all, they completely leave the market in the long-run, until either positive or normal profits are made, at which point they can re-enter the market.

In the graph below, we have a particular firm that is earning a loss in the short-run but is still operating. As a result of this situation, in the long-run, we will see individual firms start to leave the industry because of the lack of profit that is available.

The graph shows that the total revenue earned would be 5) but the total costs are 12), so they are earning an economic loss of 90 (vertical difference between ATC and AVC, $9, multiplied by the quantity, 10). Since their fixed costs are greater than their economic losses, and AVC < Price, they will continue to operate rather than shut down. However, we will see firms start to leave this industry as there is no potential for profits.

In the situation where the firm is earning a profit in the short run, we will see the attraction of new firms to the industry since there is potential to earn a profit. In the graph below, we see that the total revenue earned by this firm is 30. This means that they are earning an economic profit of $20, making other firms interested in entering this industry.

What Happens To The Market When Firms Enter or Exit?

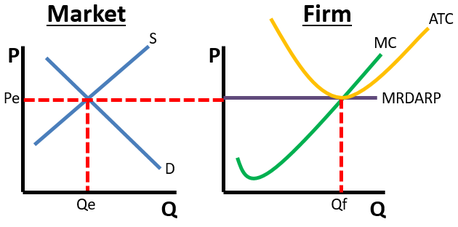

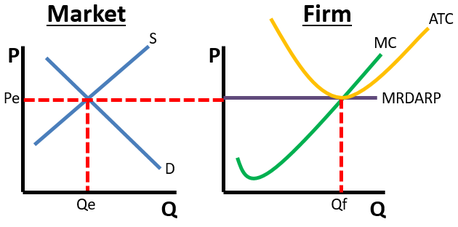

Because all perfectly-competitive firms are price takers, the market is impacted when firms enter and/or exit. This can be seen by looking at the side by side graph for a perfectly competitive market:

Price is determined by the equilibrum price in the market, so any shifts in S or D will lead to a reduction or increase in MR = D= AR = P.

When a firm enters the market, supply will shift right. This will decrease our price, driving MR = D = AR = P down.

Conversely, when a firm leaves the market, supply will shift left. This will increase our price, driving MR = D = AR = P up.

Because firms only enter when profitable and leave when losing, in the long run, profits will equilibrate to be normal. This is because if profits are present, the price will eventually be driven down, decreasing revenue and eventually profits will fall to zero. If losses are present, the price will eventually be driven up, increasing revenue and eventually profits will rise to zero. This will be elaborated on in 3.7.

<< Hide Menu

3.6 Firms' Short-Run Decisions to Produce and Long-Run Decisions to Enter or Exit a Market

5 min read•june 18, 2024

Jeanne Stansak

dylan_black_2025

Jeanne Stansak

dylan_black_2025

Entering and Exiting a Market

A perfectly-competitive market is a market marked by a few key points. This section will focus on the fact that a perfectly-competitive market has many sellers and low barriers to entry. This means that, in theory, anyone can open their own business in a perfectly-competitive market, and anyone can leave the market at will. This section will help us understand how and why a firm may enter or exit a market, but first, let's get some definitions in place.

A firm enters a market when it opens business and begins selling product. That is, when their quantity isn't 0. A firm exiting the market is not the same as completely going out of business. Instead, a firm exiting a market means the firm has decided not to produce any quantity. The actual firm may still "exist," but for our purposes exiting a market means you don't produce anything.

The Shut-Down Rule

In the short-run, firms will decide to operate or shut down by comparing total revenue to total variable cost, or price to average variable cost (AVC). This is because in the short run, there will always be a fixed cost regardless of quantity, even if quantity is zero. They will shut down when the price of the good or service drops below the average variable cost. We call this the shutdown rule, which states that the firm should continue to operate as long as the price is equal to or above the AVC.

In the graph above, you can see that at the profit maximizing (MR = MC) quantity of 10, the price is below the AVC of $7. Based on the shutdown rule, this particular firm would choose not to operate and, instead, pay their fixed costs because that would be less than its overall costs if it were to continue to operate.

This can be summed up in the following:

If you cannot cover your costs for producing goods, then you shouldn't produce any goods at all. Instead, take the hit on your fixed costs only.

Let's look at this using specific numbers. The total revenue this firm makes when it produces at the profit maximizing point is 5 x 10). The total costs are 12 x 10). If it chooses to operate they would incur an economic loss of 50 - 70). However, if they choose to shut down, they would only be responsible for their fixed costs, which in this case would be 50.

Remember the vertical difference between the ATC and AVC represents the AFC and that is how we determine that the AFC is 12-50, which is less than their economic loss if they chose to continue to operate.

Fun fact! This is out of scope for AP Micro, but producer surplus for a firm is actually exactly equal to their variable profit. That is, PS = TR - VC (not TC). When price is less than variable cost in a perfectly competitive market, the firm will have negative producer surplus - that is, they lose surplus! This is part of why the shut-down rule exists.

Long-Run Decisions to Enter or Exit the Market

When a firm is earning either a profit or a loss in the short run, it serves as a guide for other firms to either enter or exit the market. If the firm is earning a loss while still continuing to operate, then we will see firms exit that particular industry in the long-run. Remember, in the long-run, all inputs are variable, meaning a firm can completely avoid their costs by exiting the market (since no costs are fixed in the long-run!). Thus, if firms are making a loss at all, they completely leave the market in the long-run, until either positive or normal profits are made, at which point they can re-enter the market.

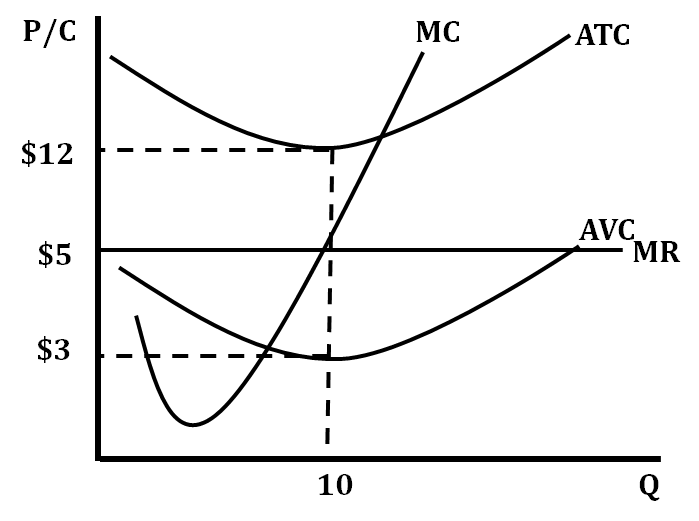

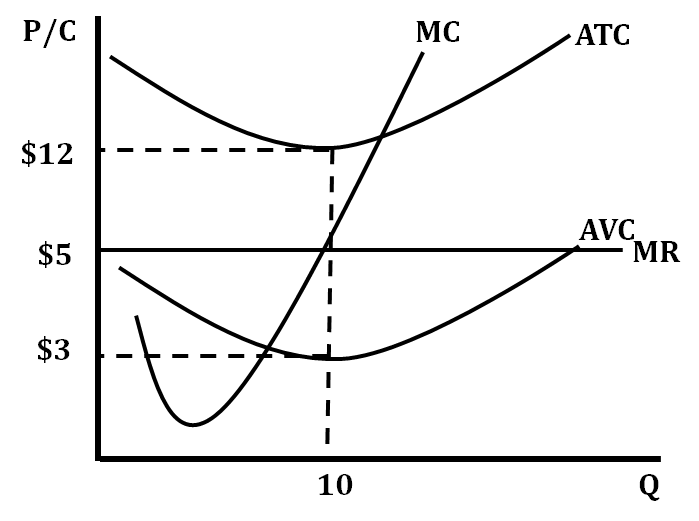

In the graph below, we have a particular firm that is earning a loss in the short-run but is still operating. As a result of this situation, in the long-run, we will see individual firms start to leave the industry because of the lack of profit that is available.

The graph shows that the total revenue earned would be 5) but the total costs are 12), so they are earning an economic loss of 90 (vertical difference between ATC and AVC, $9, multiplied by the quantity, 10). Since their fixed costs are greater than their economic losses, and AVC < Price, they will continue to operate rather than shut down. However, we will see firms start to leave this industry as there is no potential for profits.

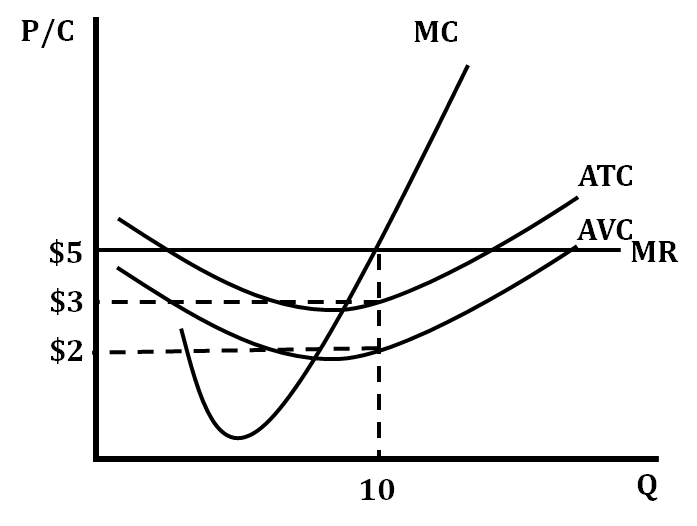

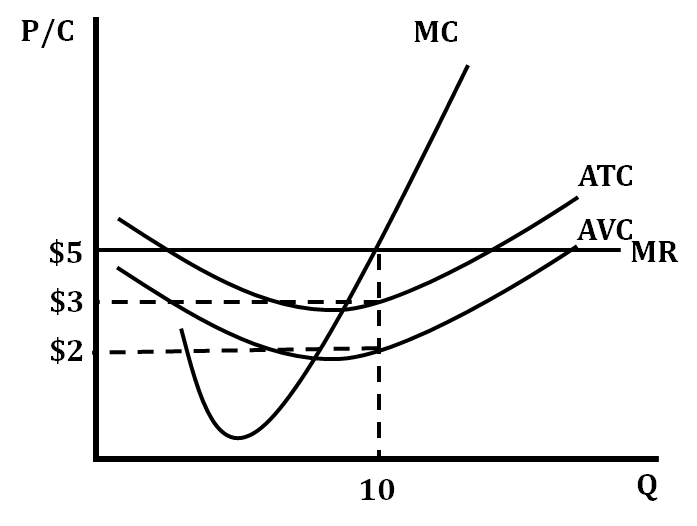

In the situation where the firm is earning a profit in the short run, we will see the attraction of new firms to the industry since there is potential to earn a profit. In the graph below, we see that the total revenue earned by this firm is 30. This means that they are earning an economic profit of $20, making other firms interested in entering this industry.

What Happens To The Market When Firms Enter or Exit?

Because all perfectly-competitive firms are price takers, the market is impacted when firms enter and/or exit. This can be seen by looking at the side by side graph for a perfectly competitive market:

Price is determined by the equilibrum price in the market, so any shifts in S or D will lead to a reduction or increase in MR = D= AR = P.

When a firm enters the market, supply will shift right. This will decrease our price, driving MR = D = AR = P down.

Conversely, when a firm leaves the market, supply will shift left. This will increase our price, driving MR = D = AR = P up.

Because firms only enter when profitable and leave when losing, in the long run, profits will equilibrate to be normal. This is because if profits are present, the price will eventually be driven down, decreasing revenue and eventually profits will fall to zero. If losses are present, the price will eventually be driven up, increasing revenue and eventually profits will rise to zero. This will be elaborated on in 3.7.

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.