Browse By Unit

Dalia Savy

Ashley Rossi

Dalia Savy

Ashley Rossi

Infants form social attachments even before they are born. As described in key concept 6.1, babies show a preference for their mother’s voice and native language. These attachment bonds, which begin before birth and strengthen after birth, are crucial to the infant’s survival. Many psychologists have studied the ways in which children form social attachments and how these social attachments influence development.

Body Contact & Harry Harlow

The earliest form of attachment, once the child is born, comes from bodily contact with the mother. Scientists have long documented the benefits of skin-to-skin contact 🥰. Not only can skin-to-skin contact help soothe the child and enhance communication, but it can (amazingly) also help the infant stabilize body temperature and even improve the function of their heart and lungs.

But what necessitates this early form of bonding? During the 1950s, Harry Harlow conducted his groundbreaking research in the area of body contact and attachment theory.

Harlow and his wife Margaret bred rhesus monkeys 🐒 for their research in learning. To prevent the spread of infection, they began separating young monkeys from their mothers early on. These young monkeys were typically put in a sterile cage with a baby blanket for warmth. Interestingly, Harlow noticed that when the blanket was removed to be laundered, the young monkeys became distressed.

This observation contradicted the theory that attachment stems from the need for nourishment. The blanket clearly offered no food or physical nourishment to the baby monkey, but they became attached to it nonetheless. Why was this? According to Harlow, this was because of the contact comfort the blanket provided.

To test this theory, an astoundingly unethical experiment was designed. Be warned, the following experiment contains elements of animal cruelty. It was later found to be unethical.

Harlow created two types of artificial mothers: one was a bare wire cylinder with a wooden head and an attached bottle for feeding (yes, it was as terrifying it sounds). The other “mother” was wrapped in terry cloth and provided no nourishment. If, in fact, attachment bonds form from the infant’s need for nourishment, then the young monkeys should prefer the wire mother with the attached bottle.

Image Courtesy of Verywell Mind.

The results suggested otherwise. Young rhesus monkeys presented with both mothers overwhelmingly preferred the comfort of the terry cloth one over the wire one, despite the fact that the cloth mother provided no food.

When the babies became stressed, they would cling to the cloth mother for comfort. When exploring, they would use the cloth mother as a secure base, returning to her every so often after venturing out.

The experiments became even more unethical. Harlow began to sequester young monkeys for months or years at a time, with no source of attachment or interaction—only food and drink. The results were troubling.

These neglected monkeys became completely catatonic and indifferent toward their environment. In adulthood, they could not properly bond or relate with other monkeys. Female monkeys could not get pregnant, since they had no interest in social interaction. Harlow had to artificially inseminate these females in order for them to reproduce.

Sadly, Harlow observed that these neglected female monkeys completely ignored their babies and neglected to feed them. In some cases, the mothers even injured or killed their babies. The implication was clear: these neglected mothers could not properly love or bond with their babies.

Harlow’s studies, as horrifying as they were, support the idea that attachment bonds stem from much more than a need for nourishment. Security, safety, comfort, and affection play fundamental roles in the attachments children form with their caregivers. The behavior of the young monkeys suggested that a need for security and safety takes precedence even over the basic need for nourishment.

More so, Harlow demonstrated that these early secure social bonds are crucial for healthy development later on. Early relationships play a key role in later adult behavior. Children who do not receive proper affection or attention may struggle to create secure relationships later in life.

Konrad Lorenz and Familiarity

In addition to contact, familiarity is also a key element in attachment. Konrad Lorenz studied a phenomenon known as imprinting, which is the rigid process by which some animals form strong and nearly immediate attachments early in life. He noted that there appeared to be a critical period in which this attachment was formed.

Lorenz studied the imprinting that took place amongst gosling ducks🐤. Since the first thing most hatchlings see is their mother, it would make sense that these ducklings naturally imprinted the female duck. However, Lorenz thought, what if the first thing they saw was not a duck at all? What if it was a particular Austrian ethologist?

Lorenz discovered that the ducks imprinted upon him, just as they would their own mothers. They followed him everywhere he went and, sure enough, this attachment was difficult to reverse.

Image Courtesy of Giphy.

Children, unlike ducklings, do not imprint. They do, however, display a preference for familiarity. Mere exposure to things fosters fondness, and children absolutely display an affinity toward things that are familiar with (whether that be eating the same food every day, repeatedly watching the same TV shows, or preferring the comfort of certain people).

Attachment Styles and Ainsworth

These ideas about attachment also raise other questions. We know children become attached, but what are the various ways in which attachments can form, and what accounts for differences in the attachment styles of different children? Developmental psychologist Mary Ainsworth was interested in this idea.

To explore different attachment styles, she developed the “strange situation” experiment in the 1970s. First, she observed mothers and their infants at home for six months in order to observe their relationships. Later, when the babies reached one year of age, she observed them in a strange situation (most typically a playroom within the laboratory).

Just like Harlow observed, infants with sensitive and responsive mothers demonstrated secure attachment. With their mother’s presence, they could confidently and comfortably explore the new playroom. However, when the mother left, they became distressed. Upon her return, they went to her seeking comfort. About 60% of children, according to Ainsworth, demonstrated this secure attachment.

Ainsworth also identified styles of insecure attachment. Some infants would cling to their mothers, refusing to explore their new surroundings. When the mother left and returned, they would either cry loudly and remain upset or appear indifferent to her return.

These insecure styles of attachment were the result of unresponsive or insensitive mothers. Furthermore, these insecure styles of attachment appear to be positively correlated with anxiety or difficulty forming trust in relationships later in life.

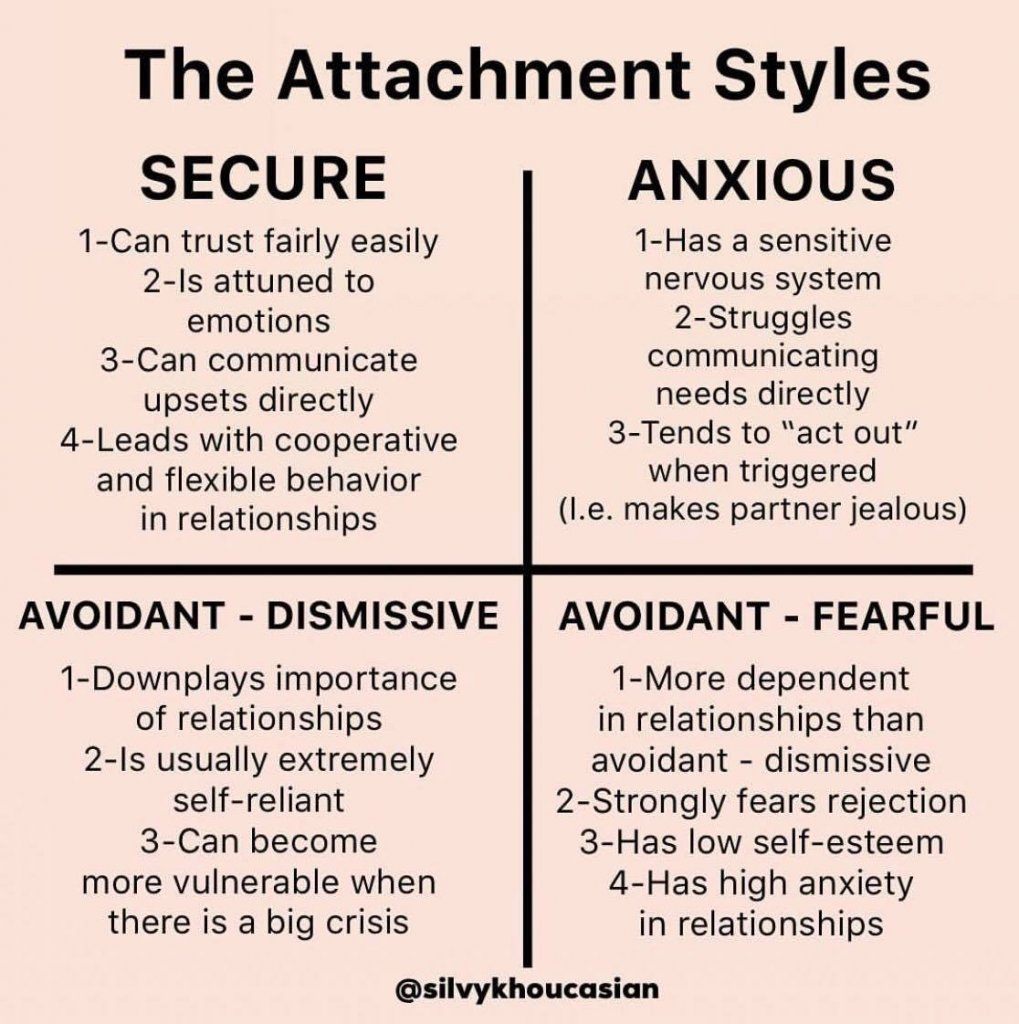

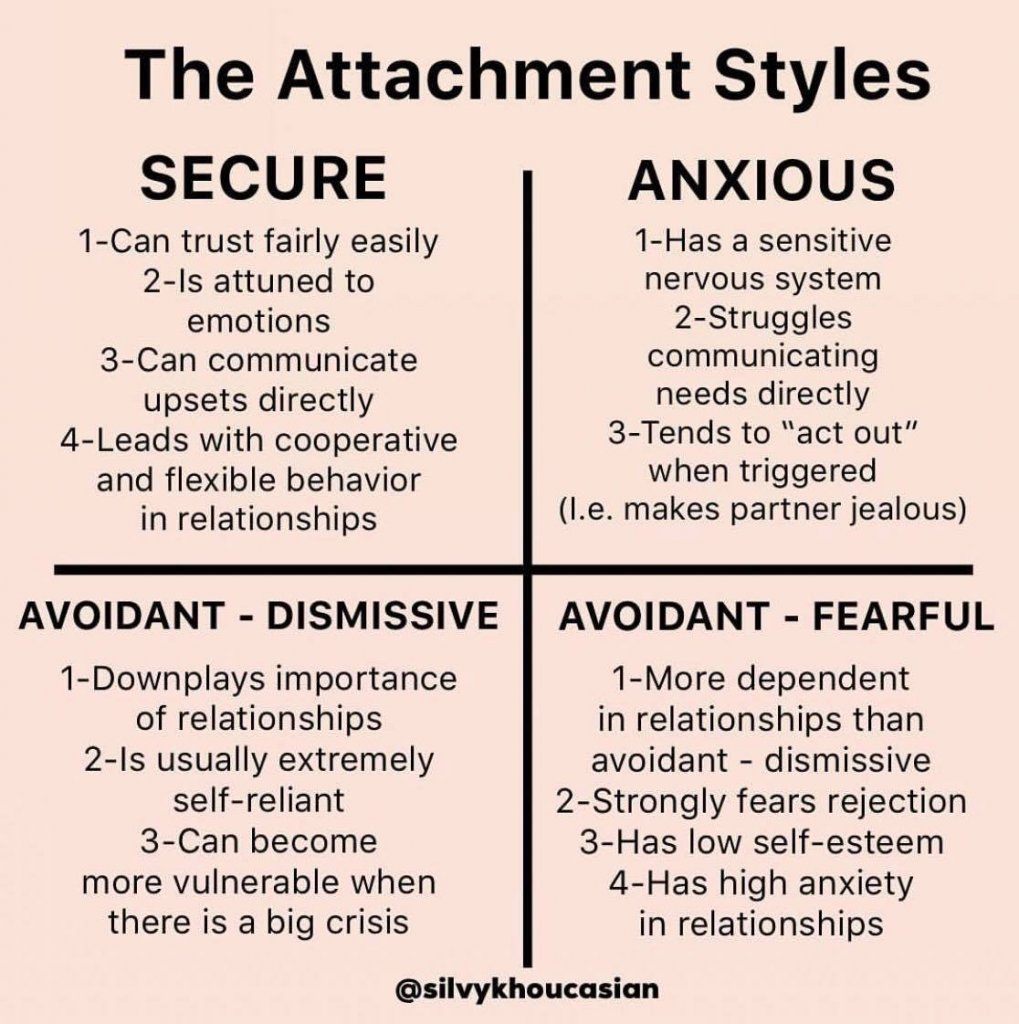

Image Courtesy of @silvykhoucasian

However, returning to the nature vs. nurture debate, there is the question of temperament, or a person’s seemingly stable pattern of emotional reactivity. Why do infants, even those born to the same parents, seemingly display varying temperaments regardless of parenting styles?

Supporting this idea, physiological differences appear to coincide with temperamental differences. In short, there appears to be a genetic link between temperament and biology (patterns of the nervous system, neurotransmitter levels, etc.). Like most things in psychology, our personalities and attachment styles appear to rely on the interaction between both nature and nurture.

Erik Erikson also focused on attachment and security through his psychosocial stages. According to Erikson, there are eight phases of psychosocial development, which last from birth until death. In the early stages of development, children learn to develop basic trust and autonomy through secure and nurturing attachments.

👉For a complete outline of Erikson’s eight stages, see key concept 6.5.

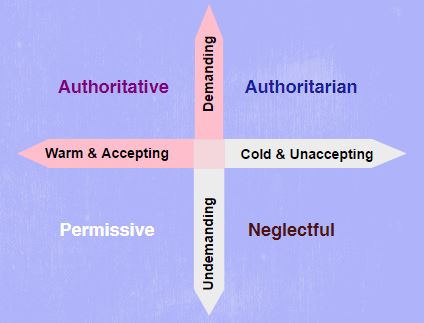

Parenting Styles and Baumrind

Another social learning theorist, Diana Baumrind, developed key theories in the area of parenting styles. Parenting is no easy feat, and parents’ approaches to rearing a child tend to vary greatly. Some parents are strict with incredibly high standards, others tend to be permissive and lax, while others are known as “helicopter 🚁 parents” who have a tendency to hover over their children closely. Which style is best?

Baumrind and her associates at UC Berkeley identified three parenting styles (which were later expanded to four):

- 👑 Authoritarian parents tend to be extremely strict and demanding, and expect blind obedience. These parents follow an almost militaristic approach to discipline and a “Why? Because I said so!” expectation of obedience.

- 💎 Authoritative parents also hold rules and expectations, and expect obedience, but do so in a more responsive way. Rules are clear and the reasoning for these rules is explained to the child. Communication is encouraged and parents are supportive of their children.

- 🐓 Permissive parents submit to their children’s desires easily. They do not hold their children to high expectations and place very few demands on their children. Children are rarely punished, even when they misbehave. It may be worth noting that later, the category of permissive parenting was later further divided. The further distinction identified permissive parenting (or indulgent parenting) and neglectful parenting.

In both situations, children face low expectations and few behavioral consequences. However, indulgent parents tend to give in to their child’s every whim, while neglectful parents tend to ignore their child’s behavior or treat it with indifference.

Baumrind concluded that children with authoritative parents grow up to be the most well-adjusted. As noted earlier, these parents develop rules and expectations, but are open about their reasoning for such. (For example, “You can’t eat cookies before dinner because you will spoil your appetite.”) They are open with their children and encourage communication and transparency. These children show the highest level of self-esteem and self-reliance**.** They also display social competence and higher academic achievement.

Authoritarian parenting is associated with lower academic performance and lower levels of self-esteem. Those with overly permissive parents tend to be impulsive, egocentric, and may have problems in later relationships.

Image Courtesy of Parenting for Brain.

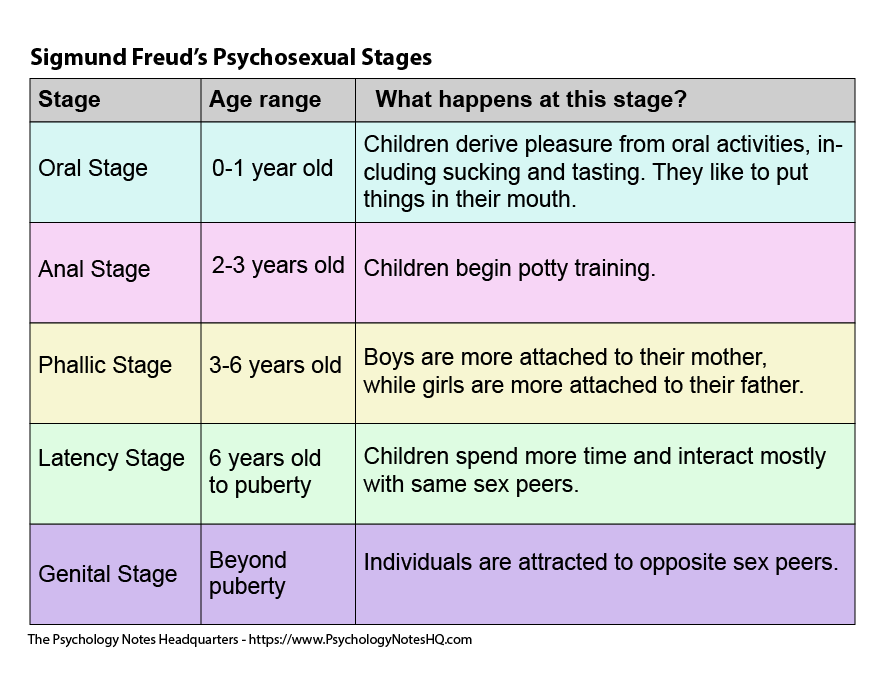

Sigmund Freud and Psychosexual Development

Within the AP Psychology curriculum, most of the information regarding Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory falls within the unit of personality. However, Freud did have a few extremely interesting ideas about development in childhood.

According to Freud’s psychosexual theory of development, infants are born with sexual and aggressive tendencies (yeah, weird) and move through a series of fixed stages as they develop.

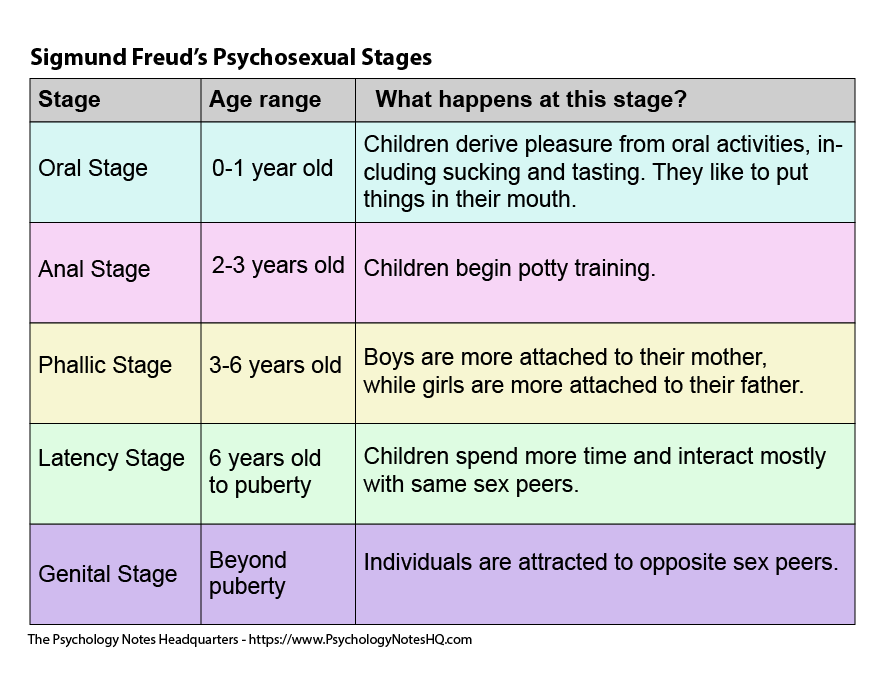

In each stage, pleasure is focused in a particular erogenous zone and development depends on the infant’s ability to resolve conflict related to that area. The stages are known as the oral stage, anal stage, phallic stage (in which the Oedipus complex occurs), latent stage, and genital stage.

Freud believed that infants may become developmentally fixated (psychologically stuck) if they are unable to resolve the conflict successfully or if conflict resolution is too traumatic. These fixations could result in a variety of developmental issues related to personality.

While Freud’s theories have been widely criticized for being overly subjective and largely disregarding the social influence of peers and cognitive factors in development, his contributions are still of great importance.

Modern-day psychologists still believe that childhood trauma (even if the individual is not consciously aware of the trauma) can stunt development in a multitude of ways. As seen through the theories previously described, traumatic experiences can follow us well into adulthood.

Image Courtesy of The Psychology Notes Headquarters

Social Learning and Albert Bandura

Albert Bandura is known for his influential work with social learning theory. In 1961, Bandura’s Bobo Doll Experiment demonstrated how children learn behavior from modeling that of adults.

In this experiment, Bandura placed children into one of three conditions. In all of the experimental conditions**,** children watched an adult interact with a large doll (a Bobo Doll).

- In the first group, children watched as the adult behaved aggressively toward the doll: throwing the doll, shouting at it, and even using a hammer in some cases.

- In the other experimental group, children were exposed to an adult who treated the doll more kindly: playing nicely or just ignoring it altogether.

- In the control group, children were exposed to no adult model. Afterward, the children were subjected to mild aggression arousal—or in other words, they were put in a situation bound to tick them off. Scientists took the children to a separate room with a lot of fancy toys. The children were told that these were the scientist’s “best toys” and that they would be reserved for other children.

So, now that these kids are nice and peeved, what will happen? Bandura found, as you may have guessed, that children who had watched the more violent adults were far more likely to imitate aggressive behaviors. The evidence is clear: children learn through observation and have a strong tendency to model the behavior they see in adults. Poor Bobo.

<< Hide Menu

Dalia Savy

Ashley Rossi

Dalia Savy

Ashley Rossi

Infants form social attachments even before they are born. As described in key concept 6.1, babies show a preference for their mother’s voice and native language. These attachment bonds, which begin before birth and strengthen after birth, are crucial to the infant’s survival. Many psychologists have studied the ways in which children form social attachments and how these social attachments influence development.

Body Contact & Harry Harlow

The earliest form of attachment, once the child is born, comes from bodily contact with the mother. Scientists have long documented the benefits of skin-to-skin contact 🥰. Not only can skin-to-skin contact help soothe the child and enhance communication, but it can (amazingly) also help the infant stabilize body temperature and even improve the function of their heart and lungs.

But what necessitates this early form of bonding? During the 1950s, Harry Harlow conducted his groundbreaking research in the area of body contact and attachment theory.

Harlow and his wife Margaret bred rhesus monkeys 🐒 for their research in learning. To prevent the spread of infection, they began separating young monkeys from their mothers early on. These young monkeys were typically put in a sterile cage with a baby blanket for warmth. Interestingly, Harlow noticed that when the blanket was removed to be laundered, the young monkeys became distressed.

This observation contradicted the theory that attachment stems from the need for nourishment. The blanket clearly offered no food or physical nourishment to the baby monkey, but they became attached to it nonetheless. Why was this? According to Harlow, this was because of the contact comfort the blanket provided.

To test this theory, an astoundingly unethical experiment was designed. Be warned, the following experiment contains elements of animal cruelty. It was later found to be unethical.

Harlow created two types of artificial mothers: one was a bare wire cylinder with a wooden head and an attached bottle for feeding (yes, it was as terrifying it sounds). The other “mother” was wrapped in terry cloth and provided no nourishment. If, in fact, attachment bonds form from the infant’s need for nourishment, then the young monkeys should prefer the wire mother with the attached bottle.

Image Courtesy of Verywell Mind.

The results suggested otherwise. Young rhesus monkeys presented with both mothers overwhelmingly preferred the comfort of the terry cloth one over the wire one, despite the fact that the cloth mother provided no food.

When the babies became stressed, they would cling to the cloth mother for comfort. When exploring, they would use the cloth mother as a secure base, returning to her every so often after venturing out.

The experiments became even more unethical. Harlow began to sequester young monkeys for months or years at a time, with no source of attachment or interaction—only food and drink. The results were troubling.

These neglected monkeys became completely catatonic and indifferent toward their environment. In adulthood, they could not properly bond or relate with other monkeys. Female monkeys could not get pregnant, since they had no interest in social interaction. Harlow had to artificially inseminate these females in order for them to reproduce.

Sadly, Harlow observed that these neglected female monkeys completely ignored their babies and neglected to feed them. In some cases, the mothers even injured or killed their babies. The implication was clear: these neglected mothers could not properly love or bond with their babies.

Harlow’s studies, as horrifying as they were, support the idea that attachment bonds stem from much more than a need for nourishment. Security, safety, comfort, and affection play fundamental roles in the attachments children form with their caregivers. The behavior of the young monkeys suggested that a need for security and safety takes precedence even over the basic need for nourishment.

More so, Harlow demonstrated that these early secure social bonds are crucial for healthy development later on. Early relationships play a key role in later adult behavior. Children who do not receive proper affection or attention may struggle to create secure relationships later in life.

Konrad Lorenz and Familiarity

In addition to contact, familiarity is also a key element in attachment. Konrad Lorenz studied a phenomenon known as imprinting, which is the rigid process by which some animals form strong and nearly immediate attachments early in life. He noted that there appeared to be a critical period in which this attachment was formed.

Lorenz studied the imprinting that took place amongst gosling ducks🐤. Since the first thing most hatchlings see is their mother, it would make sense that these ducklings naturally imprinted the female duck. However, Lorenz thought, what if the first thing they saw was not a duck at all? What if it was a particular Austrian ethologist?

Lorenz discovered that the ducks imprinted upon him, just as they would their own mothers. They followed him everywhere he went and, sure enough, this attachment was difficult to reverse.

Image Courtesy of Giphy.

Children, unlike ducklings, do not imprint. They do, however, display a preference for familiarity. Mere exposure to things fosters fondness, and children absolutely display an affinity toward things that are familiar with (whether that be eating the same food every day, repeatedly watching the same TV shows, or preferring the comfort of certain people).

Attachment Styles and Ainsworth

These ideas about attachment also raise other questions. We know children become attached, but what are the various ways in which attachments can form, and what accounts for differences in the attachment styles of different children? Developmental psychologist Mary Ainsworth was interested in this idea.

To explore different attachment styles, she developed the “strange situation” experiment in the 1970s. First, she observed mothers and their infants at home for six months in order to observe their relationships. Later, when the babies reached one year of age, she observed them in a strange situation (most typically a playroom within the laboratory).

Just like Harlow observed, infants with sensitive and responsive mothers demonstrated secure attachment. With their mother’s presence, they could confidently and comfortably explore the new playroom. However, when the mother left, they became distressed. Upon her return, they went to her seeking comfort. About 60% of children, according to Ainsworth, demonstrated this secure attachment.

Ainsworth also identified styles of insecure attachment. Some infants would cling to their mothers, refusing to explore their new surroundings. When the mother left and returned, they would either cry loudly and remain upset or appear indifferent to her return.

These insecure styles of attachment were the result of unresponsive or insensitive mothers. Furthermore, these insecure styles of attachment appear to be positively correlated with anxiety or difficulty forming trust in relationships later in life.

Image Courtesy of @silvykhoucasian

However, returning to the nature vs. nurture debate, there is the question of temperament, or a person’s seemingly stable pattern of emotional reactivity. Why do infants, even those born to the same parents, seemingly display varying temperaments regardless of parenting styles?

Supporting this idea, physiological differences appear to coincide with temperamental differences. In short, there appears to be a genetic link between temperament and biology (patterns of the nervous system, neurotransmitter levels, etc.). Like most things in psychology, our personalities and attachment styles appear to rely on the interaction between both nature and nurture.

Erik Erikson also focused on attachment and security through his psychosocial stages. According to Erikson, there are eight phases of psychosocial development, which last from birth until death. In the early stages of development, children learn to develop basic trust and autonomy through secure and nurturing attachments.

👉For a complete outline of Erikson’s eight stages, see key concept 6.5.

Parenting Styles and Baumrind

Another social learning theorist, Diana Baumrind, developed key theories in the area of parenting styles. Parenting is no easy feat, and parents’ approaches to rearing a child tend to vary greatly. Some parents are strict with incredibly high standards, others tend to be permissive and lax, while others are known as “helicopter 🚁 parents” who have a tendency to hover over their children closely. Which style is best?

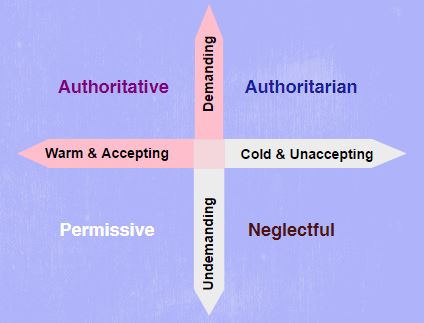

Baumrind and her associates at UC Berkeley identified three parenting styles (which were later expanded to four):

- 👑 Authoritarian parents tend to be extremely strict and demanding, and expect blind obedience. These parents follow an almost militaristic approach to discipline and a “Why? Because I said so!” expectation of obedience.

- 💎 Authoritative parents also hold rules and expectations, and expect obedience, but do so in a more responsive way. Rules are clear and the reasoning for these rules is explained to the child. Communication is encouraged and parents are supportive of their children.

- 🐓 Permissive parents submit to their children’s desires easily. They do not hold their children to high expectations and place very few demands on their children. Children are rarely punished, even when they misbehave. It may be worth noting that later, the category of permissive parenting was later further divided. The further distinction identified permissive parenting (or indulgent parenting) and neglectful parenting.

In both situations, children face low expectations and few behavioral consequences. However, indulgent parents tend to give in to their child’s every whim, while neglectful parents tend to ignore their child’s behavior or treat it with indifference.

Baumrind concluded that children with authoritative parents grow up to be the most well-adjusted. As noted earlier, these parents develop rules and expectations, but are open about their reasoning for such. (For example, “You can’t eat cookies before dinner because you will spoil your appetite.”) They are open with their children and encourage communication and transparency. These children show the highest level of self-esteem and self-reliance**.** They also display social competence and higher academic achievement.

Authoritarian parenting is associated with lower academic performance and lower levels of self-esteem. Those with overly permissive parents tend to be impulsive, egocentric, and may have problems in later relationships.

Image Courtesy of Parenting for Brain.

Sigmund Freud and Psychosexual Development

Within the AP Psychology curriculum, most of the information regarding Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory falls within the unit of personality. However, Freud did have a few extremely interesting ideas about development in childhood.

According to Freud’s psychosexual theory of development, infants are born with sexual and aggressive tendencies (yeah, weird) and move through a series of fixed stages as they develop.

In each stage, pleasure is focused in a particular erogenous zone and development depends on the infant’s ability to resolve conflict related to that area. The stages are known as the oral stage, anal stage, phallic stage (in which the Oedipus complex occurs), latent stage, and genital stage.

Freud believed that infants may become developmentally fixated (psychologically stuck) if they are unable to resolve the conflict successfully or if conflict resolution is too traumatic. These fixations could result in a variety of developmental issues related to personality.

While Freud’s theories have been widely criticized for being overly subjective and largely disregarding the social influence of peers and cognitive factors in development, his contributions are still of great importance.

Modern-day psychologists still believe that childhood trauma (even if the individual is not consciously aware of the trauma) can stunt development in a multitude of ways. As seen through the theories previously described, traumatic experiences can follow us well into adulthood.

Image Courtesy of The Psychology Notes Headquarters

Social Learning and Albert Bandura

Albert Bandura is known for his influential work with social learning theory. In 1961, Bandura’s Bobo Doll Experiment demonstrated how children learn behavior from modeling that of adults.

In this experiment, Bandura placed children into one of three conditions. In all of the experimental conditions**,** children watched an adult interact with a large doll (a Bobo Doll).

- In the first group, children watched as the adult behaved aggressively toward the doll: throwing the doll, shouting at it, and even using a hammer in some cases.

- In the other experimental group, children were exposed to an adult who treated the doll more kindly: playing nicely or just ignoring it altogether.

- In the control group, children were exposed to no adult model. Afterward, the children were subjected to mild aggression arousal—or in other words, they were put in a situation bound to tick them off. Scientists took the children to a separate room with a lot of fancy toys. The children were told that these were the scientist’s “best toys” and that they would be reserved for other children.

So, now that these kids are nice and peeved, what will happen? Bandura found, as you may have guessed, that children who had watched the more violent adults were far more likely to imitate aggressive behaviors. The evidence is clear: children learn through observation and have a strong tendency to model the behavior they see in adults. Poor Bobo.

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.